|

MARKS,

ENGELS I LENJIN O

OKOLIŠU I RAZVOJU (1/2) |

|

|

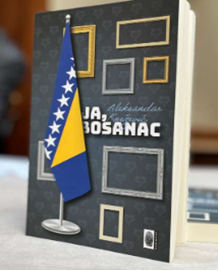

| Aleksandar Knežević |

|

Ne laskajmo sebi

suviše zbog naših ljudskih pobjeda nad prirodom Ali ne

laskajmo sebi suviše zbog naših ljudskih pobeda nad prirodom. Za svaku takvu

pobedu ona nam se sveti. Istina, svaka od njih ima u prvom redu one

posljedice na koje smo mi računali, ali u drugom i trećem redu ona ima sasvim

druge, nepredviđene posledice, koje veoma često poništavaju one prve. Ljudi

koji su u Mesopotamiji, Grčkoj, Maloj Aziji i drugde iskrčili šume da bi

dobili ziratnu zemlju nisu ni sanjali da su time položili temelje sadašnjoj

pustoši tih zemalja, lišivši ih zajedno sa šumama i centara za skupljanje i

zadržavanje vlage. Kad su alpski Italijani na južnim padinama planina

iskrčili jelove šume, tako brižljivo čuvane na severnim padinama, nisu ni

slutili da su time posjekli korjen planinskom stočarstvu na svome području;

još manje su slutili da su time svojim planinskim izvorima oduzeli vodu za

najveći deo godine, da bi ti izvori za vrijeme kiša mogli izlivati na ravnicu

još bešnje bujice. Ljudi koji su rasprostranjivali krompir po Evropi nisu

znali da s tim brašnjastim gomoljikama ujedno rasprostranjuju i skrofulozu. I

tako nas činjenice na svakom koraku podsjećaju na to da mi nipošto ne vladamo

prirodom kao što osvajač vlada tuđim narodom, kao neko ko stoji izvan

prirode, nego da svojim mesom, krvlju i mozgom njoj pripadamo i usred nje stojimo,

i da se sva naša vlast nad njom sastoji u tome što nad svim ostalim

stvorovima imamo to preimućstvo da možemo saznavati i pravilno primenjivati

njene zakone. I mi, u

stvari, svakim danom učimo da tačnije razumevamo njene zakone i da saznajemo

bliže i dalje posledice naših zahvata u uobičajeni tok prirode. Osobito

poslije ogromnih uspjeha prirodnih nauka u ovom vijeku, mi smo sve više u

stanju da upoznajemo, a time i

savlađujemo i udaljenije prirodne posledice bar najobičnijih naših operacija

u oblasti proizvodnje. I ukoliko se više to bude dešavalo, utoliko će više

ljudi ne samo opet osećati nego i znati da čine jedinstvo s prirodom. I životinje svojom

djelatnošću mijenjaju prirodu Životinje, kao

što smo već pomenuli, takođe menjaju svojom delatnošću spoljnu prirodu, iako

ne u onolikoj meri kao čovek, i to njihovo menjanje okoline vrši opet, kao

što smo videli, povratan uticaj na svoje uzročnike, izazivajući kod njih promene. Jer se u prirodi ništa ne

zbiva izolovano. Svaka pojava utiče na drugu, i obrnuto i u većini slučajeva

baš zaboravljanje tog svestranog kretanja i uzajamnog delovanja sprečava naše

prirodnjake da jasno vide najjednostavnije stvari. Videli smo kako koze

ometaju ponovno pošumljavanje Grčke; na Svetoj Jeleni uspele su koze i svinje,

koje su onamo dovezli prvi moreplovci, da staru vegetaciju ostrva gotovo

potpuno unište, i tako su pripremile tle za širenje onih biljaka koje su tamo

doneli kasnije pomorci i kolonisti. Ali kad životinje trajno deluju na svoju

okolinu, to se događa nenamerno, i to je, za same te životinje, nešto

slučajno. Ukoliko se ljudi više udaljavaju od životinja, utoliko njihovo

delovanje na prirodu sve više dobija karakter smišljenog, planskog delovanja

prema određenim, unapred poznatim ciljevima. Životinja uništava vegetaciju

jednog predela ne znajući šta radi. Čovek je uništava da bi na oslobođenom

tlu sejao žitarice ili sadio drveće i vinovu lozu, za koje zna da će mu

doneti rod koji nekoliko puta premašuje ono što je posejao ili posadio. On

prenosi korisne biljke i domaće životinje iz jedne zemlje u drugu i tako

menja floru i faunu čitavih delova sveta. Rad je pre svega

proces između čoveka i prirode Rad je pre

svega proces između čoveka i prirode, proces u kome čovek svojom sopstvenom

aktivnošću omogućuje, reguliše i nadzire svoju razmenu materije s prirodom.

Prema prirodnoj materiji on sam istupa kao prirodna sila. On pokreće prirodne

snage svoga tijela, ruke i noge, glavu i šaku da bi prirodnu materiju

prilagodio sebi u obliku upotrebljivom za njegov život. Time što ovim

kretanjem djeluje na prirodu izvan sebe i mijenja je on ujedno mijenja i

svoju sopstvenu prirodu. On razvija snage koje u njoj dremaju, i potčinjava

njihovu igru svojoj vlasti. Ne radi se ovde o prvim životinjskim

instinktivnim oblicima rada. Ono stanje kad se ljudski rad još nije bio

otresao prvog nagonskog oblika daleko je zaostalo u maglama prastarih vremena

za stanjem kad radnik istupa na robnom tržištu kao prodavač sopstvene radne

snage. Mi pretpostavljamo rad u obliku kakav je svojstven samo čoveku. Pauk

vrši operacije slične tkačevim, a gradnjom svojih voštanih komora pčela

postiđuje ponekad ljudskog graditelja. Ali što unapred odvaja i

najgorega graditelja od najbolje pčele jeste da je on svoju komoru izgradio u

glavi pre no što će je izgraditi u vosku. Na završetku procesa rada izlazi

rezultat kakav je na početku procesa već postojao u radnikovoj zamisli, dakle

idealno. Ne postiže on samo promjenu oblika prirodnih stvari; on u njima

ujedno ostvaruje i svoju svrhu koja mu je poznata, koja poput zakona određuje

put i način njegova rađenja, i kojoj mora da potčini svoju volju. A ovo

potčinjavanje nije usamljen čin. Pored naprezanja organa koji rade, traži se

za sve vreme trajanja rada i svrsishodna volja, koja se očituje kao pažnja, i

to tim više što radnika manje bude privlačila sadržina samog rada i način

njegovog izvođenja, dakle što manje on bude uživao u radu kao u igri svojih

sopstvenih telesnih i duhovnih sila. Ukoliko radnik više

osvaja vanjski svijet, utoliko više oduzima sebi životna sredstva Radnik postaje

utoliko siromašniji ukoliko proizvodi više bogatstva, ukoliko njegova

proizvodnja dobiva više na moći i opsegu. Radnik postaje utoliko jeftinija

roba ukoliko stvara više robe. Povećanjem vrijednosti svijeta stvari

raste obezvrjeđivanje čovjekova svijeta u upravnom razmjeru. Rad ne

proizvodi samo robe; on proizvodi sebe sama i radnika kao robu, i to u

razmjeru u kojem uopće proizvodi robe. Ta činjenica izražava samo ovo: da se

predmet proizveden radom, njegov proizvod, suprotstavlja njemu kao tuđe

biće, kao sila nezavisna od proizvođača. Proizvod rada jest rad

koji se fiksirao u jednom predmetu, koji je postao stvar, to je opredmećenje

rada. Ostvarenje [Verwirklichung] rada jest njegovo opredmećenje. Ovo

ostvarenje rada pojavljuje se u nacionalnoekonomskom stanju kao obestvarenje

[Entwirklichung] radnika, opredmećenje kao gubitak i ropstvo predmeta, prisvajanje

kao otuđenje, kao ospoljenje. Ostvarenje

rada toliko se pojavljuje kao obestvarenje, da se radnik obestvaruje do smrti

od gladi. Opredmećenje se toliko pojavljuje kao gubitak predmeta, da je

radnik lišen najnužnijih predmeta, ne samo predmeta za život nego i predmeta

rada. Štoviše, sam rad postaje predmet kojeg se radnik može domoći samo

najvećim naporom i sasvim neredovnim prekidima. Prisvajanje predmeta

pojavljuje se do te mjere kao otuđenje, da ukoliko radnik proizvodi više

predmeta, utoliko može manje posjedovati i utoliko više dospijeva pod vlast

svog proizvoda, kapitala. Sve te

konsekvencije nalaze se u određenju da se radnik prema proizvodu svoga

rada odnosi kao prema tuđem predmetu. Jer prema toj pretpostavci

je jasno: ukoliko se radnik svojim radom više eksteriorizuje, utoliko moćniji

postaje tuđi, predmetni svijet koji on stvara sebi nasuprot, utoliko postaje

siromašniji on sam, njegov unutrašnji svijet, utoliko njemu samome manje

pripada. Razmotrimo sad

pobliže opredmećenje, proizvodnju radnika i u njoj otuđenje,

gubitak predmeta, njegova proizvoda. Radnik ne može

ništa stvarati bez prirode, bez osjetilnog vanjskog svijeta. To

je materijal na kojem se ostvaruje njegov rad, u kojemu je on djelatan, iz

kojega i pomoću kojega on proizvodi. Kao što

priroda, međutim, pruža radu životna sredstva u smislu da rad ne može živjeti

bez predmeta na kojima se vrši, tako ona, s druge strane, pruža i životna

sredstva u užem smislu, naime sredstva za fizičko izdržavanje samog radnika. Dakle, ukoliko

radnik pomoću svoga rada više osvaja vanjski svijet, osjetilnu

prirodu, utoliko više oduzima sebi životna sredstva u dva smisla:

prvo, tako što osjetilni svijet sve više prestaje da bude predmet koji

pripada njegovu radu, životno sredstvo njegova rada; drugo, što

vanjski svijet sve više prestaje da bude životno sredstvo u

neposrednom smislu, sredstvo za fizičko izdržavanje radnika. Nastaviće se

|

|

Let us not flatter ourselves too much for our human

victories over nature But let us not flatter

ourselves too much for our human victories over nature. For every such

victory, nature takes revenge on us. True, each of them has in the first

place the consequences on which we counted, but in the second and third place

it has quite different, unforeseen consequences, which very often cancel out

the first ones. The people who in Mesopotamia, Greece, Asia Minor and

elsewhere cleared the forests to obtain arable land did not even dream that

they were thereby laying the foundations of the present desolation of those

lands, depriving them, together with the forests, of the centers for the

collection and retention of moisture. When the Alpine Italians cleared the

fir forests on the southern slopes of the mountains, so carefully guarded on

the northern slopes, they did not even suspect that they were thereby cutting

off the roots of mountain cattle breeding in their area; still less did they

suspect that they had thereby deprived their mountain springs of water for

the greater part of the year, so that during the rains these springs might

pour down even more furious torrents upon the plain. The people who spread

potatoes throughout Europe did not know that with these floury tubers they

were also spreading scrofula. And so facts remind us at every step that we do

not rule nature as a conqueror rules a foreign people, as someone standing

outside of nature, but that with our flesh, blood, and brain we belong to it

and stand in its midst, and that all our power over it consists in the fact

that we have the advantage over all other creatures of being able to know and

correctly apply its laws. And we are, in fact,

learning every day to understand its laws more accurately and to learn the

closer and more distant consequences of our interventions in the ordinary

course of nature. Especially after the enormous successes of natural science

in this century, we are increasingly able to recognize and thus overcome the

more distant natural consequences of even our most ordinary operations in the

field of production. And the more this happens, the more people will not only

feel again but also know that they are one with nature. Animals also change nature by their activity Animals, as we have

already mentioned, also change external nature by their activity, although

not to the same extent as man, and this change of their environment again, as

we have seen, has a reciprocal effect on its causes, causing changes in them.

For nothing happens in nature in isolation. Each phenomenon affects another,

and vice versa, and in most cases it is precisely the forgetting of this

versatile movement and mutual action that prevents our naturalists from

seeing the simplest things clearly. We have seen how goats hinder the

reforestation of Greece; on St. Helena the goats and pigs, which were brought

there by the first sailors, succeeded in almost completely destroying the old

vegetation of the island, and thus prepared the ground for the spread of

those plants that were brought there later by sailors and colonists. But when

animals permanently affect their environment, this happens unintentionally,

and it is, for the animals themselves, something accidental. The more people

move away from animals, the more their action on nature takes on the

character of deliberate, planned action towards certain, known goals. An

animal destroys the vegetation of a region without knowing what it is doing.

Man destroys it in order to sow grain on the liberated soil or plant trees

and vines, which he knows will bring him a harvest that several times exceeds

what he sowed or planted. He transfers useful plants and domestic animals

from one country to another and thus changes the flora and fauna of entire

parts of the world. Work is above all a process between man and nature Work is above all a

process between man and nature, a process in which man, by his own activity,

enables, regulates, and controls his exchange of matter with nature. He

himself appears as a natural force towards natural matter. He sets in motion

the natural forces of his body, arms and legs, head and hand, in order to

adapt natural matter to himself in a form usable for his life. By acting on

nature outside himself and changing it through this movement, he also changes

his own nature. He develops the forces that lie dormant in it and

subordinates their play to his own power. We are not talking here about the

first instinctive forms of animal labor. The state when human labor had not

yet shaken off the first instinctive form is far behind in the mists of ancient

times the state when the worker appears on the commodity market as a seller

of his own labor power. We assume labor in a form that is peculiar only to

man. The spider performs operations similar to those of a weaver, and by

building its wax chambers, the bee sometimes puts the human builder to shame.

But what distinguishes even the worst builder from the best bee in advance is

that he has built his chamber in his head before he builds it in wax. At the

end of the work process, the result emerges which already existed in the

worker's imagination at the beginning of the process, that is, ideally. He

does not merely achieve a change in the form of natural things; he also

realizes in them his purpose which is known to him, which, like a law,

determines the path and manner of his work, and to which he must subordinate

his will. And this subordination is not an isolated act. In addition to the

exertion of the working organs, a purposeful will is also required throughout

the duration of the work, which manifests itself as attention, and this is

all the more so the less the worker is attracted by the content of the work

itself and the manner of its execution, that is, the less he enjoys work as a

play of his own physical and mental powers. The more the worker conquers the external world, the

more he deprives himself of the means of life The worker becomes the

poorer the more wealth he produces, the more his production gains in power

and scope. The worker becomes the cheaper commodity the more he creates. With

the increase in the value of the world of things, the devaluation of the

world of man increases in direct proportion. Labor does not only produce

commodities; it produces itself and the worker as a commodity, and this in

proportion to the extent to which it produces commodities at all. This fact

expresses only this: that the object produced by labor, its product,

confronts it as an alien being, as a force independent of the producer. The

product of labor is labor that has become fixed in an object, that has become

a thing, that is, the objectification of labor. The realization

[Verwirklichung] of labor is its objectification. This realization of labor

appears in the national economic situation as the derealization

[Entwirklichung] of the worker, objectification as the loss and slavery of

the object, appropriation as alienation, as alienation. The realization of

labor appears to such an extent as derealization that the worker is

derealized to the point of starvation. Objectification appears to such an

extent as the loss of the object that the worker is deprived of the most

necessary objects, not only objects of life but also objects of labor.

Moreover, work itself becomes an object that the worker can achieve only with

the greatest effort and quite irregular interruptions. Appropriation of

objects appears to such an extent as alienation, that if the worker produces

more objects, the less he can own and the more he comes under the control of

his product, capital. All these consequences

are found in the determination that the worker treats the product of his work

as someone else's object. Because according to that assumption it is clear:

if the worker exteriorizes himself more with his work, the more powerful he

becomes, the object world he creates in opposition to himself, the poorer he

himself becomes, his inner world, the less he belongs to himself. Let's now take a

closer look at reification, the production of the worker and in it the

alienation, the loss of the object, its product. The worker cannot

create anything without nature, without the sensory external world. It is the

material on which his work is realized, in which he is active, from which and

with which he produces. Just as nature,

however, provides labor with means of life in the sense that work cannot live

without the objects on which it is performed, so it, on the other hand, also

provides means of life in a narrower sense, namely the means for the physical

support of the worker himself. Therefore, if the

worker through his work conquers the external world, the sensory nature, the

more he takes away his means of life in two senses: first, by the fact that

the sensible world ceases more and more to be an object that belongs to his

work, the means of life of his work; secondly, as the outside world increasingly

ceases to be a means of life in the immediate sense, a means for the physical

support of workers. To be continued .

|